Verithrax2007-07-11 00:58:54

QUOTE(daganev @ Jul 10 2007, 02:34 AM) 424274

You are using words which describe things which are not made up of atoms or protons or quarks.

You assume that materialism is the same as believing exclusively in things which can be quantified as matter. You are wrong, and thus I feel compelled to say you're ignorant about philosophy.

Verithrax2007-07-11 01:08:05

QUOTE(daganev @ Jul 10 2007, 06:44 PM) 424489

Just wanted to comment that my basis of trust is in the uncanny ability for my 2,000 year old tradition to accurately predict and understand human behavior today. In short, it is from my experience of it. And I imagine it is from people's experience of their own things which leads them to believe or not believe. And not any of the outside evidence of artifacts or rational arguments.

So basically, the basis for your trust is the fact that human beings behave the same way as they did 2,000 years ago, and thus a book about people born 2,000 years ago can retain some modicum of relevance today? That's like saying Copernicus is a prophet because 500 years after his death, the earth still goes around the sun...

Xavius2007-07-11 02:02:56

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 10 2007, 07:07 PM) 424523

The problem here, though, is not that you believe that empiricists can also use logic (although that belief causes problems with the whole "all knowledge arises from perception" issue), but rather that, on the one hand, you claim a position of epistemic supremacy for empiricism, and on the other hand, you say that empiricism is trustworthy on the basis of non-empirical evidence.

So, what I want to know is, why is it not ok to offer non-empirical evidence for propositions? Because you seem to be doing that exact thing. And if it is ok to have non-empirical reasons for holding to something, then you'll need to conduct your discussion about religious thought somewhat differently.

So, what I want to know is, why is it not ok to offer non-empirical evidence for propositions? Because you seem to be doing that exact thing. And if it is ok to have non-empirical reasons for holding to something, then you'll need to conduct your discussion about religious thought somewhat differently.

Perhaps you're still misunderstanding me.

Perception is the root of all reliable human knowledge. Perception is not the entirety of all reliable human knowledge.

Why does math get a free pass but the al-Ghazalian doctrine of angelic causation get ignored? Math has its roots in perception. If you throw the rock in your left hand and the rock in your right hand at the officer, you have thrown two rocks. It doesn't matter if you're an enraged Greenpeace lackey throwing apricot-sized rocks at a security guard or an enraged Palestinian throwing grapefruit-sized rocks at an Israeli soldier: if you throw one rock and one more rock, you have thrown two rocks. This is a natural category of phenomena symbolically described as 1 + 1 = 2. Using your triangle example from earlier...if people took protractors to a variety of triangles and found the sum of their angles to not be 180 degrees within a degree of accuracy reasonable for the precision with which the triangle was drawn and the protractor measures, we know that something would be wrong with the math and it would cease to be a mathematic principle (or empiricists would denounce that particular theorem). The fact that some of its principles are derived from airtight logic is fine. It still describes that which is real.

Al-Ghazali was also talking about perceived things, but his idea is completely outside of his observations. Wool burns, thus, God sent his angel to go burn it. Water flows, thus, God sent his angels to keep the water moving. If I hit you, God sent an angel to me to move my fist and an angel to you to cause you pain. He's never seen an angel, he's never seen evidence of an angel, and he glosses over highly disparate events based on an assertion that an angry desert god he has never perceived could kick his finite hide off of his camel on a whim, even though he's never actually known a deity to take the time to send an angel to unsaddle someone without recourse to a low-hanging branch.

At no point did I deny rationalist interpretation to the religious crowd. Instead, I denied suspension of disbelief for religious texts and argument from unperceived and untested premises (Unmoved Mover) or strained analogies (Watchmaker). Analogies make for great illustration or emotional impact and hypotheses are great launching pads for discovery, but for an argument to be convincing, you should be able to start from something else.

EDIT: And as a side note, without prompting, Daganev did it. The validity of his conclusion might be shaky, but that's really as simple as it is, and if we could get our Brazilian friend to trim the vitriol, we could set about giving the argument a proper thrashing.

Unknown2007-07-11 14:31:31

@Blastron: I'm not sure that we'd mean the same thing, but I actually agree with what you said.

I understand you; I'm just demonstrating how you can't consistently maintain what you're saying.

Counting depends on perception, yes, because counting, by definition, is enumerating objects. So, when I've thrown one rock and thrown another rock, I have thrown two rocks. All you've done here is proven that something that is an empirical activity by definition is... an empirical activity.

Math that does not depend on the enumeration of objects, however, does not arise from empiricism, nor do the laws of logic, nor does the statement, "Empiricism is the only way to decide what can and cannot be true." In fact, I could probably list a near-infinitely long list of statements like, "The square root of 9 is 3" or "Attacking a person's character does not speak to the truth or falsity of their arguments," or "It's morally wrong for priests to molest children under their care," that you would probably estimate as true or false, and while you might use empirical analogies to illustrate your point, you couldn't -prove- them with empirical data.

Your point about triangles (heh, get it?) is also the wrong way 'round. No protractor in the world has ever measured an actual triangle and yielded an angular total of 180 degrees. The mathematical definition of a triangle is 180 degrees. In fact, it is the mathematical definition which provides our point (heh, I'm on a roll!) of reference for what a material triangle -should- be. If we scrap the mathematical definition and make the empirical data our basis for geometric knowledge, we could have a figure whose angles added to 176 degrees, another whose angles added to 218 degrees, and they could both be triangles. Or not.

Either: triangles are figures whose angles add to 180 degrees, or they are figures whose angles add to some number kind of close to 180 degrees. Your own assertion is that this deviance is the result of limitations in accuracy in both protractors and constructed triangles. But how do you know that? That didn't come from observation - observation yields the -inaccurate- data. You are -siding- with the purely rational definition of a triangle and using that to make judgments about your protractor and the shape of your musical instrument; if you sided with the empirical data, you'd say, "These triangles are real. Protractors are real. The mathematical definition of a triangle, being patently unreal, needs revision in order to comply with observed data."

Or, you could say, "Mathematically defined triangles have these properties. Constructed triangles have those properties. They're pretty close. Neither system is infallible. I can still build a bridge. Life goes on." Personally, I like that route, but it's not open to your current position.

It's your insistence that empiricism is the final arbiter of what is and is not true that's killing you, here, and as Blastron rightfully pointed out, it puts you in an impossible epistemic position.

As has been amply demonstrated through the thread, you espouse a totalized principle (i.e. Empiricism is the only way to decide between competing knowledge claims.) that you cannot prove (in fact, the closest you've come to summoning a proof for it has been, by your own statement, non-empirical) and do not (and I would argue, cannot) live out, consistently, as your feelings about protractors illustrate.

On an unrelated note, I never thought I would say a phrase like that last bit, but such are the wonders of debate.

Don't make me go back and find the "You cannot rely on arguments from philosophy" post.

This is what the sticking point is for me in this discussion. I don't care if you're an empiricist or not. I like Daganev just fine, but I'm not in this for his benefit. I even like Verithrax and Roark, most of the time.

The sticking point for me is that you are demanding that religious people prove their beliefs using criteria that you cannot use to prove your own beliefs, either. You have had ample opportunity to do so. Your tenets for your belief contradict the belief itself, being non-empirical in nature. Your trust in your belief is based on the assumption that the belief is already true. You cannot summon empirical proof for your belief, just as there are any number of claims that you would label as "knowledge" for which you cannot summon empirical proof.

Despite the fact that both you and I have repeatedly demonstrated the accuracy of this critique over the past few days, you seem unwilling to take the next logical step and apply it to how you evaluate other systems that produce knowledge claims in comparison to your own. For reasons that are clearly not empirical in nature, you insist, despite the obvious flaws (and inherent impossibilities), on maintaining that empiricism sits on a privileged epistemic position where it escapes the liabilities and limitations that all the other systems (except yours) have, which is very fundamentalist behavior. Blind faithish. I know you to be a stalwart opponent of both, and I'm not sure why you aren't seeing the trend in your own argumentation.

If you would stop insisting that theistic thought meet your personal standards for what can and cannot be true while you yourself consistently fail to meet those standards, then I would pretty much be done and could get back to making witty comments in the Rants thread.

QUOTE(Xavius @ Jul 10 2007, 09:02 PM) 424564

Perhaps you're still misunderstanding me.

Perception is the root of all reliable human knowledge. Perception is not the entirety of all reliable human knowledge.

Why does math get a free pass but the al-Ghazalian doctrine of angelic causation get ignored? Math has its roots in perception. If you throw the rock in your left hand and the rock in your right hand at the officer, you have thrown two rocks. It doesn't matter if you're an enraged Greenpeace lackey throwing apricot-sized rocks at a security guard or an enraged Palestinian throwing grapefruit-sized rocks at an Israeli soldier: if you throw one rock and one more rock, you have thrown two rocks. This is a natural category of phenomena symbolically described as 1 + 1 = 2. Using your triangle example from earlier...if people took protractors to a variety of triangles and found the sum of their angles to not be 180 degrees within a degree of accuracy reasonable for the precision with which the triangle was drawn and the protractor measures, we know that something would be wrong with the math and it would cease to be a mathematic principle (or empiricists would denounce that particular theorem). The fact that some of its principles are derived from airtight logic is fine. It still describes that which is real.

Perception is the root of all reliable human knowledge. Perception is not the entirety of all reliable human knowledge.

Why does math get a free pass but the al-Ghazalian doctrine of angelic causation get ignored? Math has its roots in perception. If you throw the rock in your left hand and the rock in your right hand at the officer, you have thrown two rocks. It doesn't matter if you're an enraged Greenpeace lackey throwing apricot-sized rocks at a security guard or an enraged Palestinian throwing grapefruit-sized rocks at an Israeli soldier: if you throw one rock and one more rock, you have thrown two rocks. This is a natural category of phenomena symbolically described as 1 + 1 = 2. Using your triangle example from earlier...if people took protractors to a variety of triangles and found the sum of their angles to not be 180 degrees within a degree of accuracy reasonable for the precision with which the triangle was drawn and the protractor measures, we know that something would be wrong with the math and it would cease to be a mathematic principle (or empiricists would denounce that particular theorem). The fact that some of its principles are derived from airtight logic is fine. It still describes that which is real.

I understand you; I'm just demonstrating how you can't consistently maintain what you're saying.

Counting depends on perception, yes, because counting, by definition, is enumerating objects. So, when I've thrown one rock and thrown another rock, I have thrown two rocks. All you've done here is proven that something that is an empirical activity by definition is... an empirical activity.

Math that does not depend on the enumeration of objects, however, does not arise from empiricism, nor do the laws of logic, nor does the statement, "Empiricism is the only way to decide what can and cannot be true." In fact, I could probably list a near-infinitely long list of statements like, "The square root of 9 is 3" or "Attacking a person's character does not speak to the truth or falsity of their arguments," or "It's morally wrong for priests to molest children under their care," that you would probably estimate as true or false, and while you might use empirical analogies to illustrate your point, you couldn't -prove- them with empirical data.

Your point about triangles (heh, get it?) is also the wrong way 'round. No protractor in the world has ever measured an actual triangle and yielded an angular total of 180 degrees. The mathematical definition of a triangle is 180 degrees. In fact, it is the mathematical definition which provides our point (heh, I'm on a roll!) of reference for what a material triangle -should- be. If we scrap the mathematical definition and make the empirical data our basis for geometric knowledge, we could have a figure whose angles added to 176 degrees, another whose angles added to 218 degrees, and they could both be triangles. Or not.

Either: triangles are figures whose angles add to 180 degrees, or they are figures whose angles add to some number kind of close to 180 degrees. Your own assertion is that this deviance is the result of limitations in accuracy in both protractors and constructed triangles. But how do you know that? That didn't come from observation - observation yields the -inaccurate- data. You are -siding- with the purely rational definition of a triangle and using that to make judgments about your protractor and the shape of your musical instrument; if you sided with the empirical data, you'd say, "These triangles are real. Protractors are real. The mathematical definition of a triangle, being patently unreal, needs revision in order to comply with observed data."

Or, you could say, "Mathematically defined triangles have these properties. Constructed triangles have those properties. They're pretty close. Neither system is infallible. I can still build a bridge. Life goes on." Personally, I like that route, but it's not open to your current position.

It's your insistence that empiricism is the final arbiter of what is and is not true that's killing you, here, and as Blastron rightfully pointed out, it puts you in an impossible epistemic position.

As has been amply demonstrated through the thread, you espouse a totalized principle (i.e. Empiricism is the only way to decide between competing knowledge claims.) that you cannot prove (in fact, the closest you've come to summoning a proof for it has been, by your own statement, non-empirical) and do not (and I would argue, cannot) live out, consistently, as your feelings about protractors illustrate.

On an unrelated note, I never thought I would say a phrase like that last bit, but such are the wonders of debate.

QUOTE

At no point did I deny rationalist interpretation to the religious crowd.

Don't make me go back and find the "You cannot rely on arguments from philosophy" post.

This is what the sticking point is for me in this discussion. I don't care if you're an empiricist or not. I like Daganev just fine, but I'm not in this for his benefit. I even like Verithrax and Roark, most of the time.

The sticking point for me is that you are demanding that religious people prove their beliefs using criteria that you cannot use to prove your own beliefs, either. You have had ample opportunity to do so. Your tenets for your belief contradict the belief itself, being non-empirical in nature. Your trust in your belief is based on the assumption that the belief is already true. You cannot summon empirical proof for your belief, just as there are any number of claims that you would label as "knowledge" for which you cannot summon empirical proof.

Despite the fact that both you and I have repeatedly demonstrated the accuracy of this critique over the past few days, you seem unwilling to take the next logical step and apply it to how you evaluate other systems that produce knowledge claims in comparison to your own. For reasons that are clearly not empirical in nature, you insist, despite the obvious flaws (and inherent impossibilities), on maintaining that empiricism sits on a privileged epistemic position where it escapes the liabilities and limitations that all the other systems (except yours) have, which is very fundamentalist behavior. Blind faithish. I know you to be a stalwart opponent of both, and I'm not sure why you aren't seeing the trend in your own argumentation.

If you would stop insisting that theistic thought meet your personal standards for what can and cannot be true while you yourself consistently fail to meet those standards, then I would pretty much be done and could get back to making witty comments in the Rants thread.

Unknown2007-07-11 15:49:54

Even though I am not big on math, I dare to say math and logic come from observation. Everything in math is derived from basic axioms which come from observation.

I don't understand why you think it's otherwise and those examples don't illustrate your point.

I don't understand why you think it's otherwise and those examples don't illustrate your point.

Unknown2007-07-11 16:41:08

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 11 2007, 04:31 AM) 424679

@Blastron: I'm not sure that we'd mean the same thing, but I actually agree with what you said.

I understand you; I'm just demonstrating how you can't consistently maintain what you're saying.

*snip*

Math that does not depend on the enumeration of objects, however, does not arise from empiricism, nor do the laws of logic, nor does the statement, "Empiricism is the only way to decide what can and cannot be true." In fact, I could probably list a near-infinitely long list of statements like, "The square root of 9 is 3" or "Attacking a person's character does not speak to the truth or falsity of their arguments," or "It's morally wrong for priests to molest children under their care," that you would probably estimate as true or false, and while you might use empirical analogies to illustrate your point, you couldn't -prove- them with empirical data.

I understand you; I'm just demonstrating how you can't consistently maintain what you're saying.

*snip*

Math that does not depend on the enumeration of objects, however, does not arise from empiricism, nor do the laws of logic, nor does the statement, "Empiricism is the only way to decide what can and cannot be true." In fact, I could probably list a near-infinitely long list of statements like, "The square root of 9 is 3" or "Attacking a person's character does not speak to the truth or falsity of their arguments," or "It's morally wrong for priests to molest children under their care," that you would probably estimate as true or false, and while you might use empirical analogies to illustrate your point, you couldn't -prove- them with empirical data.

Hm, perhaps I am not understanding you, then. Is your argument that empiricism is not the source of all knowledge? If so, then I completely agree with you. While we can use empirical methods to gain knowledge, we also gain knowledge through other sources.

However, determining the validity of this knowledge is an empirical task. All of your examples can be empirically proved or disproved. If we are capable of quantifying something and manipulating it, even as a thought exercise, we are capable of coming to an empirical conclusion about it. Indeed, this is the core of the scientific method: we come up with a hypothesis and seek to empirically prove it.

In short, empirical knowledge is not the only form of knowledge, nor is it the source of knowledge, but since it is provable, it tends to be more reliable than other forms of knowledge.

Daganev2007-07-11 17:03:51

QUOTE(Verithrax @ Jul 10 2007, 06:08 PM) 424544

So basically, the basis for your trust is the fact that human beings behave the same way as they did 2,000 years ago, and thus a book about people born 2,000 years ago can retain some modicum of relevance today? That's like saying Copernicus is a prophet because 500 years after his death, the earth still goes around the sun...

If only.

I am not aware of any other system today which so completely accounts for all types of people in all types of situations.

Daganev2007-07-11 17:05:14

QUOTE(Verithrax @ Jul 10 2007, 05:58 PM) 424542

You assume that materialism is the same as believing exclusively in things which can be quantified as matter. You are wrong, and thus I feel compelled to say you're ignorant about philosophy.

Then please explain it. I've never held of materialism so its likely I'm misunderstanding how its really believed. Though I wouldn't say I'm ignorant about philosophy, just materialism (since I don't believe in it)

Unknown2007-07-11 17:44:30

@Kashim: Assertions are not arguments.

Show me the observable data for square roots, truly parallel lines, pi, truth tables, imaginary numbers, negative numbers... that last one is a fun one. Show me negative five rocks. Or take a picture of some lines you believe to be parallel and empirically prove that, if extended in both directions, they would never intersect. I will also accept a photo of an object that is pi X unit distance away from another object, assuming you can also empirically explain how you know the distance is pi.

I think you and I do agree on this point. This is part of my argument. All knowledge does not arise from empiricism.

Then do so. Since all of my examples can be empirically proven or disproven, then empirically --prove-- or disprove that a triangle's angles add up to 180 degrees. Or that it's immoral to molest a child. Or that ad hominem attacks are invalid reasoning. Or that historical figures ever existed. I'm hearing from the pro-empiricist side that all of these examples I keep bringing up obviously depend on empirical evidence, but nobody seems very keen to produce this evidence.

The problem becomes compounded when we turn this demand back onto the assumptions of empiricism, itself. Using empiricism to justify empiricism is question begging. So... what do we do, then?

In short, empirical knowledge is not the only form of knowledge, nor is it the source of knowledge, but since it is provable, it tends to be more reliable than other forms of knowledge.

Empirical knowledge is empirically provable (although the validity of empiricism's assumptions is not, including the assumption that empiricism is the best way to decide what can and cannot be true). Yes. Mathematical claims can be proven through math. Logical claims can be proven through logic. Claims made by the Old Testament can be proven by the Old Testament.

What these systems all have in common is that: A) They, ultimately, rest on an assumption or set of assumptions that cannot be proven, B ) They cannot be validated outside themselves, and C) The systems verify their own results, and thus themselves. If, for the sake of argument, we decided that empiricism's validity was something we'd need to establish before trusting it, how would you do it? Empirically?

Show me the observable data for square roots, truly parallel lines, pi, truth tables, imaginary numbers, negative numbers... that last one is a fun one. Show me negative five rocks. Or take a picture of some lines you believe to be parallel and empirically prove that, if extended in both directions, they would never intersect. I will also accept a photo of an object that is pi X unit distance away from another object, assuming you can also empirically explain how you know the distance is pi.

QUOTE(blastron @ Jul 11 2007, 11:41 AM) 424701

Hm, perhaps I am not understanding you, then. Is your argument that empiricism is not the source of all knowledge? If so, then I completely agree with you. While we can use empirical methods to gain knowledge, we also gain knowledge through other sources.

I think you and I do agree on this point. This is part of my argument. All knowledge does not arise from empiricism.

QUOTE

However, determining the validity of this knowledge is an empirical task. All of your examples can be empirically proved or disproved.

Then do so. Since all of my examples can be empirically proven or disproven, then empirically --prove-- or disprove that a triangle's angles add up to 180 degrees. Or that it's immoral to molest a child. Or that ad hominem attacks are invalid reasoning. Or that historical figures ever existed. I'm hearing from the pro-empiricist side that all of these examples I keep bringing up obviously depend on empirical evidence, but nobody seems very keen to produce this evidence.

The problem becomes compounded when we turn this demand back onto the assumptions of empiricism, itself. Using empiricism to justify empiricism is question begging. So... what do we do, then?

QUOTE

If we are capable of quantifying something and manipulating it, even as a thought exercise, we are capable of coming to an empirical conclusion about it. Indeed, this is the core of the scientific method: we come up with a hypothesis and seek to empirically prove it.

Except for the fact that something that exists only mentally obviously cannot be subject to empirical verification, sure. Objects that are quantifiable and manipulatable are, indeed, empirical and excellent candidates for empirical inquiry. It does not follow, however, that because one can gain empirical knowledge from empirical methods exercised on empirically accessible objects that, ergo, empiricism is the final word on what can and cannot be the case.QUOTE

In short, empirical knowledge is not the only form of knowledge, nor is it the source of knowledge, but since it is provable, it tends to be more reliable than other forms of knowledge.

Empirical knowledge is empirically provable (although the validity of empiricism's assumptions is not, including the assumption that empiricism is the best way to decide what can and cannot be true). Yes. Mathematical claims can be proven through math. Logical claims can be proven through logic. Claims made by the Old Testament can be proven by the Old Testament.

What these systems all have in common is that: A) They, ultimately, rest on an assumption or set of assumptions that cannot be proven, B ) They cannot be validated outside themselves, and C) The systems verify their own results, and thus themselves. If, for the sake of argument, we decided that empiricism's validity was something we'd need to establish before trusting it, how would you do it? Empirically?

Unknown2007-07-11 18:47:36

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 11 2007, 07:44 PM) 424720

Show me the observable data for square roots, truly parallel lines, pi, truth tables, imaginary numbers, negative numbers... that last one is a fun one. Show me negative five rocks. Or take a picture of some lines you believe to be parallel and empirically prove that, if extended in both directions, they would never intersect. I will also accept a photo of an object that is pi X unit distance away from another object, assuming you can also empirically explain how you know the distance is pi.

This is demagogy. You don't prove mathematical objects but mathematical laws.

Everything in mathematics is being proven through mathematics and logic. Everything in mathematics and logic though, is derived from axioms. Axioms are considered true based on obvervation, meaning empirical ways. So your claim that math is proven by math is not true, because it is proven, in its core, by empirical means that led to formulating those axioms.

Unknown2007-07-11 18:51:01

QUOTE(Kashim @ Jul 11 2007, 01:47 PM) 424743

This is demagogy. You don't prove mathematical objects but mathematical laws.

Everything in mathematics is being proven through mathematics and logic. Everything in mathematics and logic though, is derived from axioms. Axioms are considered true based on obvervation, meaning empirical ways. So your claim that math is proven by math is not true, because it is proven, in its core, by empirical means that led to formulating those axioms.

Everything in mathematics is being proven through mathematics and logic. Everything in mathematics and logic though, is derived from axioms. Axioms are considered true based on obvervation, meaning empirical ways. So your claim that math is proven by math is not true, because it is proven, in its core, by empirical means that led to formulating those axioms.

You keep just saying things and not proving them. Talk about demagogy.

Show me! Show me the empirical evidence for the things I mentioned. It's quite simple.

Unknown2007-07-11 19:07:29

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 11 2007, 08:51 PM) 424746

You keep just saying things and not proving them. Talk about demagogy.

Show me! Show me the empirical evidence for the things I mentioned. It's quite simple.

Show me! Show me the empirical evidence for the things I mentioned. It's quite simple.

How am I supposed to show you that -5 is true? Negative number itself is not something that is subject to proving. Any kind of law including a negative number is. So, when I have 6 rocks, and I take 5 rocks, I have one rock left. How is this not empirical?

Everything in math that is considered true has been proven by math and logic, down to the axioms. Do you not believe that? Show me I'm wrong and I'll concede. Don't require of me a degree in mathematics to prove every mathematics law you throw at me.

Unknown2007-07-11 19:12:02

QUOTE(Kashim @ Jul 11 2007, 02:07 PM) 424754

How am I supposed to show you that -5 is true? Negative number itself is not something that is subject to proving. Any kind of law including a negative number is. So, when I have 6 rocks, and I take 5 rocks, I have one rock left. How is this not empirical?

Because you aren't adding negative five rocks. You're taking away positive five rocks.

Let's do this one instead to make it easier for you. What's negative three plus negative four? What's the empirical basis for that? Or, what's the empirical basis for the axioms that let you solve that problem?

QUOTE

Everything in math that is considered true has been proven by math and logic. Do you not believe that?

QUOTE

Mathematical claims can be proven through math. Logical claims can be proven through logic.

And that's the post that got your undergarments in a conflated state and you charged that these things all have empirical foundations? In fact, you said that ALL my examples have empirical proof. And this is your third post, and you STILL haven't produced a single shred of empirical evidence.

I'm starting to see a strong trend from your side of the fence.

Verithrax2007-07-11 19:25:06

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 11 2007, 11:31 AM) 424679

About mathematics not being observable...

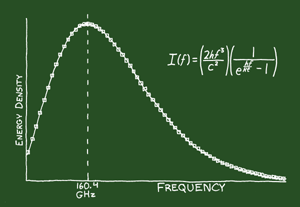

Mathematics, like many things in science, is a model. Rather than being an absolute truth or a system of facts which we take to be true based on evidence (Like most scientific theories in some fields) it is rather an abstract construct which is useful both as a language for expressing models of the behaviour of things in the universe and making predictions. However:

I hope you're familiar with this. To make a long story short, the line in the graph is what was predicted by theoretical physicists, using mathematics to extrapolate from much earlier data. The dots are the actual observations made by the COBE mission probe. Probably one of the most striking demonstrations of the predictive power of mathematics.

Verithrax2007-07-11 19:34:24

QUOTE(daganev @ Jul 11 2007, 02:05 PM) 424705

Then please explain it. I've never held of materialism so its likely I'm misunderstanding how its really believed. Though I wouldn't say I'm ignorant about philosophy, just materialism (since I don't believe in it)

The question of whether consciousness or love exists is answerable in that, while they have no direct material form, they do exist as the state of matter - in the same way that what I'm typing now exists, of course. It doesn't have any material representation, but it exists as the state of electrons in a variety of devices (Rather than on the relative position of atoms in the universe.)

Totally abstract concepts like truth and justice can be understood the same way (The concept exists as the state of our brains) and as being useful symbols for talking about things; if we didn't "believe" in the existence of truth and justice (And therefore weren't able to qualify things are true or just) life would be harder to live, thus we believe in them without actually believing there's some ultimate arbiter of truth or a personification of justice. Things like morality and truth value are concepts which we attach to ideas; we attach a certain truth value to most claims we can think of, meaning that we, based on the evidence we have access to or simply on our less-rational thought processes, understand it as being a real statement about the universe. We attach a moral value to actions based on our own internal moral compass (Which you'll not is exceedingly similar between cultures; no human culture exists in which murder, theft or perjury are acceptable.) or some philosophically built system of morality. Usually, it's either some variation on utilitarianism, which simply defines "immoral" as "causing suffering" - and as suffering really exists and can in some cases even be roughly quantified, is grounded in reality - or Kant's categorical imperative. Either can be argued as a model for constructing a functioning society.

Unknown2007-07-11 20:02:30

QUOTE(Demetrios @ Jul 11 2007, 09:12 PM) 424760

Because you aren't adding negative five rocks. You're taking away positive five rocks.

Let's do this one instead to make it easier for you. What's negative three plus negative four? What's the empirical basis for that? Or, what's the empirical basis for the axioms that let you solve that problem?

You mean like when I said this two posts ago?

And that's the post that got your undergarments in a conflated state and you charged that these things all have empirical foundations? In fact, you said that ALL my examples have empirical proof. And this is your third post, and you STILL haven't produced a single shred of empirical evidence.

I'm starting to see a strong trend from your side of the fence.

Let's do this one instead to make it easier for you. What's negative three plus negative four? What's the empirical basis for that? Or, what's the empirical basis for the axioms that let you solve that problem?

You mean like when I said this two posts ago?

And that's the post that got your undergarments in a conflated state and you charged that these things all have empirical foundations? In fact, you said that ALL my examples have empirical proof. And this is your third post, and you STILL haven't produced a single shred of empirical evidence.

I'm starting to see a strong trend from your side of the fence.

Demetrios, adding negative numbers and subtracting positive numbers is the same thing.

The empirical example you demand is very simple. "I owe my neighbour 3 chickens. Wolf ate them and my neighbour borrowed me another 4. So I owe him 7 chickens now."

You said math is only proven by itself without any outside verification. I say that math is being proven by math and logic rules that come from empirical means. There's a difference.

Even the most abstract and complicated mathematical law come long way from the very basic axioms. If every step of deduction is proven (and since axioms are true by empirical observation) then the final conclusion is true.

As I said, I won't prove all of your examples because I am not a mathematician, and even if I was I wouldn't, because it would probably take a lot of time, space and energy to prove it all the way down.

Answer me if you consider it true, or not. Otherwise I will assume you're just playing with words.

Also, if you think it is not true, provide a proof.

I am also not sure if it's ok putting me on some side of the fence, note that I am only discussing the math issue.

Unknown2007-07-11 20:48:50

QUOTE(Kashim @ Jul 11 2007, 03:02 PM) 424780

Demetrios, adding negative numbers and subtracting positive numbers is the same thing.

No, it isn't. Negative numbers and positive numbers have different identities, which is sort of the point. You can't observe negative numbers.

QUOTE

The empirical example you demand is very simple. "I owe my neighbour 3 chickens. Wolf ate them and my neighbour borrowed me another 4. So I owe him 7 chickens now."

I didn't follow that example at all. What chickens did the wolf eat? And did your neighbor borrow negative four chickens from you? How'd that happen?That aside, you still haven't done it. The "chickens" you propose are theoretical chickens (or, more dramatically, Chickens of Pure Logical Construction) that do not exist because their quantity is less than zero. They are not chickens that you observed. As soon as a quantity drops to zero, it is no longer available for observation or manipulation. I admit I'm a little flummoxed at how someone can contest this.

QUOTE

You said math is only proven by itself without any outside verification. I say that math is being proven by math and logic rules that come from empirical means. There's a difference.

Well, in the first place, all you asked me in your last post was if I believed math was proven by math and logic, which obviously I do, since I was the one that said it, first.

Now, if you're asking me if I think the laws of logic and higher math come from observation and people work their way backward from that, or if all them have empirical correlations that prove them, then no, no I don't, and nearly every empiricist up to Husserl agrees with me. Heck, it took many cultures centuries upon centuries to come up with "zero." Do you think none of them had ever observed the experience of... not having any more of something? What they were lacking was the rational entity of "zero."

I have never seen 999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999 of anything, and you probably haven't either, and I would even go out on a limb and bet that no one has. Yet, both of us can add, subtract, etc. from this number and perform all kinds of operations on it with no correlation to any observable experience whatsoever. No one has observed parallel lines, but we can conceive of them and operate with them. You might argue that I could, in my head, imagine five of something, then five more of something, then on and on until I get to a number that large, but nobody does math that way.

In fact, mathematics has numbers explicitly labeled as imaginary numbers to represent some of the constructs that are so theoretical, they don't even fit in with our common usage of numerical symbols.

QUOTE

Even the most abstract and complicated mathematical law come long way from the very basic axioms. If every step of deduction is proven (and since axioms are true by empirical observation) then the final conclusion is true.

First of all, empiricism is inductive, not deductive. Deduction is a theoretical process that reasons from premises. Reasoning from your experience is inductive and establishes probability. It goes like this:"Every time I've dropped an object, it's always fallen to the ground. Therefore, objects will naturally fall to the ground."

Math and logic, by contrast, are -necessarily- true if performed without error. 3 + 4 = 7 and always will, no matter what science finds or how the planet might change.

Second of all, you're assuming the truth of your conclusion in your argument, thus:

QUOTE

Even the most abstract and complicated mathematical law come long way from the very basic axioms. If every step of deduction is proven (and since axioms are true by empirical observation) then the final conclusion is true.

That's the very idea that's being debated, here. You can't use your argument as a foundation for why your argument is true.

QUOTE

As I said, I won't prove all of your examples because I am not a mathematician, and even if I was I wouldn't, because it would probably take a lot of time, space and energy to prove it all the way down.

I'm not a mathematician, either, and I would say that the sentiment, "I can't refute you, but I'm sure somebody out there could," is neither empirically proven nor a good reason for maintaining an argument. I could just as easily say, "I won't prove to you everything in the Bible is true, because I'm not a theologian, and even if I were, it would probably take a lot of time, space, and energy to prove it all the way down." Would you accept that?Incidentally, time and energy cannot be empirically proven. I'll give you space, although some empiricists would not.

QUOTE

Answer me if you consider it true, or not. Otherwise I will assume you're just playing with words.

Also, if you think it is not true, provide a proof.

Also, if you think it is not true, provide a proof.

First of all, I'm not in the business of believing things because I can't disprove them. I can't disprove that there's a planet somewhere in the universe that's made of cream cheese, either, but I'm not going to start sending bagels to NASA.

However, in this case, I have provided a multitude of examples of things that we claim are knowledge that can't be empirically proven, and so far the best candidate I've got by way of refutation is a story about my neighbor borrowing chickens from me that I don't have because a wolf ate some chickens I owed him.

QUOTE

I am also not sure if it's ok putting me on some side of the fence, note that I am only discussing the math issue.

Now, -that- is a good point. Fair enough, and I apologize.

Tajalli2007-07-11 21:09:11

QUOTE

"That's the very idea that's being debated, here. You can't use your argument as a foundation for why your argument is true."

Much like the 'rule' of sorts; That a definition of a word can't include the word in the definition - yes?

Hazar2007-07-11 21:22:18

You're all assuming math is empirical.

Horseshit.

It's a theoretical construction based around postulates.

Physics - some of physics is empirical.

Horseshit.

It's a theoretical construction based around postulates.

Physics - some of physics is empirical.

Tajalli2007-07-11 21:34:29

I know that math isn't empirical. My response was to connect to something I knew a bit better, phrase wise. It was something I learned in ESL. I think that why math is becoming part of the debate, right now, is that (at least from what I've followed along with) it is being taken as empirical, so that is now a diversion from the topic.